Margaret Gordon

The remarkable and inspirational Mrs Margaret Hope Maberly Gordon, B.E.M. (1910 - 1999).

Heroine of No. 4 lifeboat (51 days), she ably supported Third Officer James Alister Whyte and cared for all aboard until, one by one, they all succumbed, leaving only Margaret and James alive on the 52nd and final day of their journey. Tragically, James Whyte lost his life on 4 March 1943 while being repatriated to the UK aboard the Ellerman Line steamer SS City of Pretoria. The ship, carrying ammunition, was torpedoed and exploded with the loss of all hands, thus making Margaret Gordon the sole survivor from No. 4 lifeboat."

I would like to acknowledge and thank the State Library of Victoria, and the Australian War Memorial.

Courtesy Sue Home

Margaret Hope Maberly Smith was born on 3 February 1910 in Colac, Victoria, Australia.

Her first calling was as a teacher and she graduated In Arts at Melbourne University, and holds the Diploma of Education. In 1934 she was teaching at Moronga Girls' School, Geelong.

In 1936, Margaret visited Quetta, India to stay with family and friends. There she met Crawford Gordon, a Scot and deputy chief-engineer with the Bengal-Assam Railways. They married the following year on 14 October 1937 at St. Thomas Cathedral, Bombay.

In 1942, the couple fled the Japanese advance in Burma by riverboat. Crawford caught dengue fever, and Margaret nursed him until she also went down with the sickness. Although she made a full recovery, he was left physically and emotionally debilitated. "The only remedy," pronounced his doctor, "is to get him out of India."

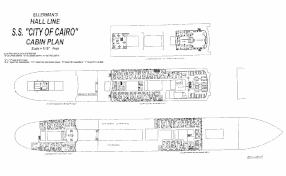

The couple secured a passage on the SS City of Cairo, an 8,000-tonne cargo/passenger ship that had seen better days but retained traces of Edwardian charm in its cabins.

There were 300 passengers and crew aboard—a uniquely war-affected group of returning elderly Indian civil servants, missionaries, judges, businessmen, young war widows, and tradesmen returning from an ill-fated British wartime glider project in India.

Ship Torpedoed

The ship sailed from Bombay on 2 October 1942, calling at Durban on 19 October and Cape Town on 27 October. She then set course for the sole South Atlantic crossing, departing Cape Town on 31 October 1942. At approximately 8:30 PM on 6 November 1942, the ship was torpedoed by U-68 under the command of Karl-Friedrich Merten.

Helping to launch boat No. 1 was volunteer boat warden Tommy Green, a Merchant Navy Chief Officer travelling as a passenger. Boats were lowered in orderly fashion to the rails on the promenade deck, and Margaret had to climb over the rail into the boat. Suddenly there was a rush for the boat by some of the Lascars, and this sudden excessive weight resulted in Tommy Green's hand and arm being trapped in the block on the davits. Some of the men had to force the Indians off the boat and back onto the deck to enable Green's arm to be released. The boat was then lowered to the water and the men began climbing down the ladder.

Just as Gordon—as Margaret called her husband—was halfway down, the Indians in the bow cast off from the ship, crying "Boat full!" Gordon went back up, and Margaret called to him to hang on.

By now, twenty minutes had elapsed and Captain Merten loosed a second torpedo to seal the fate of the SS City of Cairo. Lifeboats 1 and 3 lay in the path of this torpedo. No. 3 was destroyed, injuring some of the occupants and throwing them into the sea. No. 1 escaped the core of the blast but lifted and turned over, pitching nearly everyone, including Margaret, into the sea. On coming to the surface, she struck out away from the ship towards another lifeboat floating a little distance away. This boat was half full of water, and she was hauled aboard. It turned out to be the same lifeboat, No. 1, which had righted itself after the second torpedo blast.

Missing

As dawn came, they took stock of the situation and some of the women and children were transferred to other boats. Margaret moved to No. 4 boat under the charge of Third Officer James "Knocker" Whyte. She continued to scan each boat for her husband, and it gradually dawned on her that he was missing.

In fact, after No. 1 boat had cast off from the ship, he had gone back on board. When the second torpedo hit and the ship started to sink rapidly, the captain ordered those still on board to go to No. 2 lifeboat, which was half full of water but still attached to the ship. Gordon was last seen boarding this boat, but it was too full of water to move away from the ship. It drifted over the well deck as the ship was sinking, and some of the men jumped into the sea and swam away to avoid being dragged down with her. It later transpired that six men were lost when the ship went down, and Crawford Gordon was never seen again. This was just the beginning of their ordeal, though—many more lives would be lost before rescue came.

In the Lifeboat

The first few days passed with the boats sailing all day and tying together at night.

No. 4 lifeboat was 21 feet long and low in the water, resulting in a low freeboard. With 22 people aboard, the boat was cramped, heavy, and difficult to manoeuvre. On the fourth day, 10 November, the men were almost exhausted, and Knocker told the captain in No. 5 boat that they were in danger of being swamped unless the load was lightened. It was agreed to redistribute some passengers, and eventually, after some changes back and forth to other boats, they were left with 17 people aboard: six European men, ten Asian men, and one woman — Margaret Gordon.

They were by now adjusting to the routine of life in the boat. The only things they were certain of were that they must try to eat as much as possible and never drink salt water.

Captain Rogerson in No. 5 boat decided that the group should now sail all night and keep in touch by flashing torches. It meant continuous watches shared in pairs and was tiresome and anxious work. Things became more difficult in the boat and it was fatally easy for the boats to get widely separated in the darkness and even in daylight. When the wind dropped, the sails had to be unreefed. It was also discovered that some of the Lascars were stealing drinking water at night and had half-emptied one of the tanks. This was quite serious, and in the commotion that followed, they somehow lost their course and lost touch with the other boats.

They spotted light signals way off in what appeared to be the wrong direction and rowed toward them. They found No. 8 boat, which had suffered a broken mast and had a badly hurt man aboard. They tied up for the night with No. 8 boat and waited for dawn. The men were exhausted and just flopped down where they were to sleep.

Margaret was the only woman in No.4 boat. Once or twice the women in No. 8 boat suggested that she come over to them, but she preferred to remain. However, Margaret did have her doubts. She sat up at night thinking how much better it would be for Knocker to have another strong, able-bodied man in the boat capable of handling oars and sails.

It was now the 14th November, against Knocker's advice, Margaret felt she had to go. Tommy Green in charge of No. 8 agreed to take her, so they arranged an exchange. A young ship's officer travelling as a passenger, Freddie Powell, volunteered to take Margaret's place. Mrs Gordon, quiet and wonderfully self-controlled, stepped over into No. 8.

However, seeing how very crowded that boat was compared with No. 4, and noticing that their arrangements for dressings and the issue of rations were well-organised, she began to feel that she had left her duty. There were things, she said, which she could do for the men — some were already in bad condition. She now felt she had only made matters worse and consequently, the next morning, she got Tommy to ask Knocker if he would take her back. He agreed and she jumped back into No. 4 again, with Fred Powell remaining there as well.

The next morning the two boats separated and went their own ways. A couple of days later, around 18 November, the first of the Indians died, and by the end of the week they had all succumbed, leaving just the Europeans.

The Europeans in this boat were:

- James Alister Whyte, Third Officer

- Tom A.V. Humphries, Second Radio Officer

- William T. Pirrie, Fourth Engineer

- William McGregor, Third Engineer

- Margaret Gordon, Passenger

- Fred Powell, Passenger (D.B.S., Third Engineer, B.I.S.N. Co.).

- William C. Solomon, Passenger

Critical Decisions

It was now around 20 November, and Knocker was working out his approximate position based on the distance travelled. He announced that if they were to hit St. Helena Island, they should be somewhat near it by now. They could have been quite close but still unable to see it.

The next day Knocker called a conference, and they had to choose whether to continue looking for St. Helena or to turn west with the wind and sail for the coast of South America, some 1,500 miles away. They all voted for the latter, as it meant sailing towards the shipping lanes and the chance of being picked up, instead of wandering about in the no-man's land of the South Atlantic. Margaret understood these were big decisions, and only Knocker had the necessary knowledge and experience to navigate the boat—a huge responsibility for someone aged only 25.

Struggle for Survival

As the days passed, the remaining Europeans started to fail, so Knocker doubled the water ration for the next fortnight, as there was no point in conserving it if they could not do without it. Despite his efforts, the men grew steadily worse. On 25 November, Freddie Powell died. "This cast a deep gloom over us all," said Margaret.

Bill Pirrie kept his strength longer than the others—he had helped Knocker at the tiller steering the boat—but now his eyesight began to fail, so Knocker taught Margaret to steer by compass, and she relieved him on watch during the daytime.

The sea anchors broke and then the sail gave out, and it took Knocker most of the day to mend it. Margaret was amazed at the perseverance and strength that Knocker could still summon when all around him were lying weak and helpless. "He was just determined to sail that boat and get somewhere."

Within a week, Bill McGregor and Bill Solomon died, leaving just four. It was now 4 December 1942, and all the days passed in much the same way. Knocker and Margaret did everything between them now. They went back to short water rations as they were on their last tank. They kept the boat sailing day and night—three-hour watches at night and shorter ones during the day when the sun was very hot. When not at the tiller, there was usually bailing to be done, and of course they tried to sleep as much as possible to conserve strength.

At night, after making the sick men comfortable, Knocker would take the first watch at sunset and get the boat set on the right course. Margaret would take over at about ten o'clock, and she was quite confident steering to a group of stars given to her by Knocker, but sometimes when it was cloudy and overcast, she had to wake him. One cloudy night he said, "All right, keep the moon over your right shoulder." On one occasion she fell asleep and suddenly woke with a start to find the moon smiling in her face and the sail flat aback. That meant waking Knocker up, and he had to get out the oars and row the boat around, which sapped his precious strength.

Margaret loved the clear tropical nights—they were beautiful. Her first watch came when the stars were bright and twinkling. Sirius, the dog-star, shone brilliantly astern, and towards morning they sailed directly into the path of the moon.

At sunrise and sunset, Knocker always tried to check with his watch—a Rolex—which had kept going on Greenwich Time and by which he could calculate their progress towards the west.

During the day they kept up much the same kind of routine. It was a strange existence. Margaret states: "We were not really companionable in that we could not talk more than necessary, and when one was at the tiller the other was usually trying to sleep. One day we recited Gray's Elegy together, but the effort left us parched with thirst."

On 18 December, Sparkie died. Knocker was very upset as they had been shipmates for so long. Bill Pirrie died two days later, and then they were quite alone.

Signs of Hope

On 22 December, a large wooden crate sailed past them, and the next day a twig floated by, so they began to be hopeful that they were at last in the shipping lanes.

On Christmas Day they drank the last of the brandy and wished each other, "Many more Christmases to come." In the afternoon they heard an aircraft flying towards them very fast, but it never spotted them. Although disappointing, it did give them hope that they were nearing civilisation. Food and water were now running short, with about a week's supply left.

At dawn on 27 December, they saw a huge black rain cloud coming fast towards them. They steered into it—the first rain in seven weeks. They sat there in the early dawn, absolutely drenched, but happy to be able to drink their fill.

Rescue

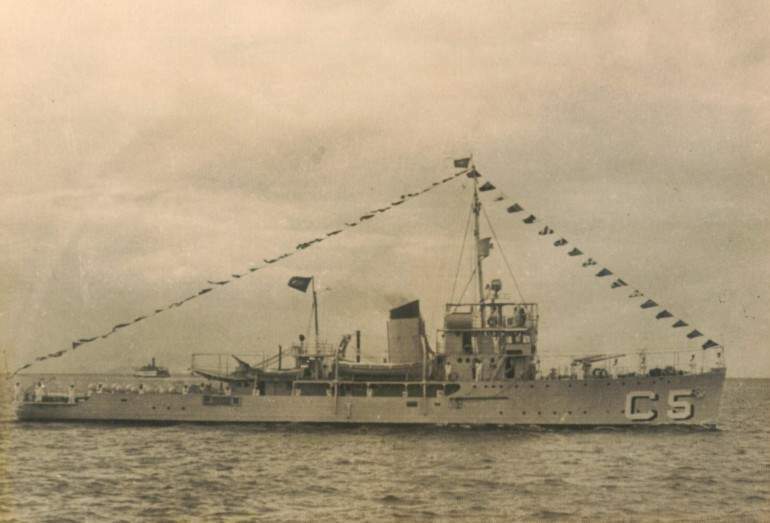

Later that same morning—their lucky day!—Margaret awoke to hear the cry, "Ships! Ships!" A whole row of ships sailing along the horizon. Flares were lit and they watched anxiously until they saw one of the ships detach itself from the convoy and come racing towards them like a greyhound. Soon they were nearly alongside and they found out it was the Brazilian Carioca-class minelayer, Caravelas.

Courtesy Ozires Moreas

Knocker still had to get out the oars and row to the ship. "God knows how he found the strength," said Margaret. The rail was lined with smiling, friendly faces and strong hands lifted them aboard and gave them mugs of coffee. They spent 51 days at sea in the lifeboat, the only two left alive, rescue came on the 52nd day. Since setting off on their own on November 13, they had covered over 2,000 miles.

Both were in a serious condition when rescued and they were taken to the Centenario Hospital in Recife where their condition steadily improved.

After the Rescue

© Australian War Memorial

In February 1943, after recuperation, Knocker Whyte sailed on the SS City of Pretoria bound for Liverpool. Tragically, the ship was torpedoed and sank with complete loss of life—the young officer who had shared those 51 days of extraordinary hardship with Margaret was lost at sea just weeks after their rescue.

In March 1943, after recovering in Recife, Margaret travelled to New York, where she took up a position as librarian in the office of the Australian Trade Commissioner.

From 1944 to 1946, she served for two years in the Women's Royal Naval Service and it was as a Wren that her courage during the ordeal was recognised with a British Empire Medal (B.E.M.) presented to her in Washington D.C. by the British Ambassador, Lord Halifax on 26 September 1944.

Citation

Passenger

British Empire Medal (Civil Division)

"The ship, sailing alone, was torpedoed in darkness. She sustained heavy damage and commenced to settle rapidly by the stern. When it was seen that the vessel could not be saved, abandonment was ordered. Many passengers and members of the crew were rescued from the sea during the night and distributed into six boats which set a course for land, 480 miles away. The Third Officer was in charge of a boat which parted company with the others after seven days. As there were no navigational instruments in this boat, land was missed and the boat was adrift for 52 days. Great suffering and hardships were endured and when the boat was eventually picked up only the Third Officer and a passenger, Mrs. Gordon, remained. Mr Whyte never gave up hope during this tremendous ordeal and, by improvisation and repairs, he kept the boat afloat and sailing. His courage and resource were outstanding. Mrs Gordon showed exceptional qualities of fortitude and endurance. When the occupants of the boat died one after another, she did all in her power to allay their sufferings. Towards the end of the voyage she kept watch with the Third Officer in sailing and steering the boat."

Margaret shunned publicity all her life and it was not until an English journalist, Ralph Barker, managed to track her down and then wrote a book about the sinking of the SS City of Cairo - "Goodnight, Sorry For Sinking You" - that her amazing story became more widely known.

For her mother, Margaret wrote a detailed chronicle describing her harrowing experience at sea. Once completed, she firmly closed the door on this chapter of her life, choosing to look ahead rather than dwell in the past.

Later Life & Legacy

© S.L.V..(MS 13372) (MS BOX 3902/9)

Margaret returned home to Sandringham, Australia in 1946, and a year later married farmer Roy Stanley Ingham in Melbourne. They farmed together at Officer, outside Melbourne and later in Benalla until Roy's death in 1959.

At the age of 50, Margaret retrained as a qualified librarian and went on to oversee children's library services throughout Victoria, dedicating herself to fostering literacy and learning for the next generation.

By the time Margaret retired in 1980 her initiative had created the largest collection of children's literature in Australia, with the Children's Research Collection as it was known then, consisting of 12,000 books. Today the State Library holds the most comprehensive collection of Australian children's literature in the world, with over 70,000 Australian and overseas children's books in its keeping, bearing testimony to Margaret's vision.

— Juliet O'Conor

Margaret Ingham died on 9 May 1999, aged 89, having lived a full life that extended far beyond those 51 days that tested the very limits of human endurance.

Read more about Margaret at the Australian War Memorial